- Home

- Billingham, Mark

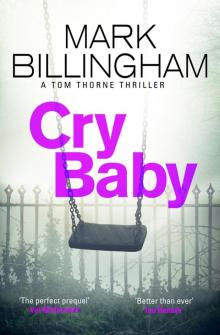

Cry Baby

Cry Baby Read online

Mark Billingham has twice won the Theakston’s Old Peculier Award for Crime Novel of the Year, and has also won a Sherlock Award for the Best Detective created by a British writer. Each of the novels featuring Detective Inspector Tom Thorne has been a Sunday Times bestseller. Sleepyhead and Scaredy Cat were made into a hit TV series on Sky 1 starring David Morrissey as Thorne, and a series based on the novels In the Dark and Time of Death was broadcast on BBC1. Mark lives in north London with his wife and two children.

Also by Mark Billingham

The DI Tom Thorne series

Sleepyhead

Scaredy Cat

Lazybones

The Burning Girl

Lifeless

Buried

Death Message

Bloodline

From the Dead

Good as Dead

The Dying Hours

The Bones Beneath

Time of Death

Love Like Blood

The Killing Habit

Their Little Secret

Other fiction

In The Dark

Rush of Blood

Cut Off

Die of Shame

<

LITTLE, BROWN

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Little, Brown

Copyright © Mark Billingham Ltd 2020

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those

clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance

to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7515-8207-9

Little, Brown

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK Company

www.hachette.co.uk

www.littlebrown.co.uk

For Claire. Twenty years on. Still chocolate . . .

Contents

PART ONE: Hide and Seek

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

PART TWO: What’s The Time, Mr Wolf?

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Thirty-Five

Thirty-Six

Thirty-Seven

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Nine

Forty

Forty-One

Forty-Two

Forty-Three

Forty-Four

Forty-Five

Forty-Six

Forty-Seven

Forty-Eight

Forty-Nine

Fifty

Fifty-One

Fifty-Two

Fifty-Three

Fifty-Four

Fifty-Five

PART THREE: Grandmother’s Footsteps

Fifty-Six

Fifty-Seven

Fifty-Eight

Fifty-Nine

Sixty

Sixty-One

Sixty-Two

Sixty-Three

Sixty-Four

Sixty-Five

Sixty-Six

Sixty-Seven

Sixty-Eight

Sixty-Nine

Seventy

Seventy-One

Seventy-Two

Seventy-Three

Seventy-Four

Seventy-Five

Seventy-Six

Seventy-Seven

Seventy-Eight

Seventy-Nine

Eighty

Eighty-One

PART FOUR: Poison

Eighty-Two

Eighty-Three

Eighty-Four

Acknowledgements

Halfway up the front door, where the shit-brown gloss is not worn away or flaking, he can see a scattering of handprints. He lets out the breath he’s been holding and leans closer. That clammy palm he had felt pressed hard against his own the previous day at the station, the calloused thumb and thick fingers; the shapes of them are all marked out perfectly against the paintwork, in brick-dust and blood.

He puts his own, far smaller hand inside one of the prints, and pushes.

The door swings open and he steps inside as quickly as always.

He stands for a few seconds in the semi-dark.

He listens and sniffs.

The music he can hear in one of the rooms further down the hall – tinny, like it’s coming from a cheap radio – is the same as he’d heard the day before leaking from the station locker room. That Eurythmics song about angels and hearts. The smells are familiar too, though a little trickier to identify immediately.

Something . . . burned or boiled dry in the kitchen. Mould blooming behind the textured wallpaper or perhaps in the bare boards beneath his feet . . . and a far richer stink that drifts down from the upper floor, growing stronger as he stands and sweats and puts an arm out to steady himself, until he can swear that he feels it settling on his face and neck like soft drizzle.

Rotting meat and wet metal.

In contrast to the hallway, the stairs are thickly carpeted and, when he takes his first step up, he feels his foot sink deep into the pile. He looks down and sees a viscous, grey-green liquid oozing up and into his shoes, then quickly lifts his head and fixes his gaze on the top step when he feels something slithering against his ankles. By the time he’s reached the landing he’s out of breath, his socks are sodden and things are moving beneath the soles of his feet. In turn, he pushes each foot hard against the floor, feels something flatten, then burst.

The bile rises into his throat and he grabs for the banister. Just for a moment it’s as though he’s about to fall backwards and tumble down the stairs behind him.

It would be all right to fall, he thinks, to keep falling. The pain would be done with quickly enough and blackness would be better than this.

Blankness.

He forces himself to take a step, turns right and moves towards the door at the far end of a corridor that narrows before it curves around the foot of a second set of stairs. There’s a converted attic above him and he knows that the three small beds it contains are neatly made, identical. There’s no point looking, because he knows too that there’s nobody up there. Time is precious, so he can’t afford to waste it.

Three plump and empty pillows, that’s all. Three pairs of furry slippers with eyes, and ears and whiskers. Three freshly laundered pillowcases, the initials embroidered in red, blue and green.

L, S, A-M.

He keeps on walking towards the big room at the front of the house, the m

aster. There are several other rooms on this floor, plenty of other doors, but he knows exactly which one he’s meant to walk through.

He knows where he’s needed.

It’s twenty feet away, more, but it’s as though he reaches the door in just a few steps and it opens as he stretches his hand towards the doorknob. A hand that he moves immediately to cover his nose and mouth.

The man sitting, legs splayed out across the hearth, looks up, as though blithely unaware that much of his face is missing and most of his brain is caked like dried porridge on the mirror above the mantelpiece. Unaware that, by rights, he should not be seeing anything. The man gently shakes what’s left of his head, a little miffed to have been kept waiting.

He says, ‘Oh, here you are.’

On the bed opposite, lying side by side, the three small figures are perfectly still. Their hair is washed and brushed, their nightdresses spotless. They’re asleep, that’s all, they must be, though it’s strange of course that the gunshot hasn’t woken them.

Wanting attention, the man in the hearth clears his throat and it rattles with blood. It’s hard to imagine he has any left, judging by the amount that’s dripping down the wall, soaking his vest, creeping across the tiles around his legs. He raises his arm and proffers the gun. Dangles it.

‘Always better to be sure,’ he says. ‘And I know how much you want to.’

There was hesitation the first time, the first few times, but now he just steps forward to calmly take what he’s being offered and leans down to press the barrel hard against the killer’s forehead. He watches it sink into the tattered white flesh, pushing through into the hollow where the man’s brain used to be.

‘Belt and braces, Tom,’ the dead man says. ‘Belt and braces . . . ’

He closes his eyes and happily squeezes the trigger.

As he recoils from the explosion, he feels the warm spatter across his cheek and his ears are singing when he turns to look towards those six white feet in a line at the end of the bed. It’s odd, of course, because he can barely hear anything, but that voice grows louder suddenly; the music that’s still coming from the kitchen below, the song about angels. No odder than anything else, all things considered, but still, he’s always aware how strange it is and how perfect.

He’s come to suppose that it’s simply because the song provides the perfect soundtrack for that moment when the youngest of the girls moans softly, then opens her eyes. When, one by one, the three of them sit up and look at him, wide-eyed, blinking and confused.

Thorne did not wake suddenly on mornings like this. There was no longer any gasping or crying out. Rather, it had become like surfacing slowly towards the light from deep under dark water, and everything stayed silent until his stubble rasped against the pillow, when he turned his head sharply to see if his wife was next to him.

Of course, she wasn’t.

Better, he thought, that Jan was no longer there, his wife in name only. He was well aware of what she’d have been likely to say, the tone of voice when she said it. He’d have heard concern, obviously, but something else that would have let him know she was weary of it and starting to run out of patience. With all sorts of things.

Same dream?

Not exactly the same.

Ten years, Tom.

It’s hardly my fault—

More than that . . .

He got dressed quickly and went downstairs. He turned on the kettle then the radio and stuck a couple of slices of bread in the toaster. Grabbing butter and Marmite from the fridge he found himself humming ‘There Must Be An Angel’, though by the time he was pouring milk into his tea he was singing along tunelessly with those two comedians from Fantasy Football League whose song seemed to be on the radio every five minutes. It was starting to get on his nerves to be honest and it didn’t help that one of them was a bloody Chelsea fan. Thorne wasn’t altogether sure that football was coming home or that thirty years of hurt was likely to end any time soon, but he was undeniably excited about the three weeks ahead.

Provided other things didn’t get in the way, of course.

Jan, and the wanker she was shacked up with.

Murder.

He’d talked to a couple of the lads at work, tried to switch his shifts around so he could watch England v Switzerland in the opening match of the tournament that afternoon, but his DI was having none of it. Thorne had done his best not to look too annoyed, but was sure it was because the man was Scottish. He guessed the miserable arsehole would be rooting for Switzerland, anyway. If things were miraculously quiet, there was always the possibility of nipping round the corner to the Oak, watching the game in there. He could find a radio, worst came to the worst.

By then, he might have stopped touching a hand to his cheek to wipe away spatter that wasn’t there, and the smell he imagined was clinging to him might have faded a little.

Not that it mattered much.

He wasn’t kidding himself.

The memory of what had actually gone on in that house was always there, of course, and, however stubbornly it might linger, the dream was very different. The wife rarely featured for reasons he couldn’t fathom, strangled downstairs in the kitchen he never ventured into. The girls had actually been found in a small bedroom at the back, side by side on the floor between bunk beds and a mattress. And crucially, of course, people did not die more than once.

Thorne carried his dirty plate, mug and knife across to the draining board. He turned off the radio. He picked up his bag and leather jacket from the chair he’d dumped them on the night before, then stepped out into the hallway.

He raised a hand, placed it flat against his front door and thought how small it looked. Those prints on that front door had been a new addition, the slimy stuff on the stairs, too. All as unpleasant as ever, but nothing he couldn’t live with, would not prefer to live with. He opened the door, squinted against the sunshine and watched for a minute as the man who lived opposite struggled to attach a flag of St George to the aerial of his car.

The man looked up and waved. ‘Easy win today, you reckon?’

Thorne said, ‘Hope so.’

Thinking: Belt and braces . . .

The dream was always so much better than the memory.

Because, in the dream, he saved them.

PART ONE

Hide and Seek

ONE

‘Sweet,’ Maria said.

Cat looked at her. ‘What?’

‘The pair of them.’ Maria leaned back on the bench and nodded towards the two boys in the playground. Her son, Josh, had just landed with a bump at the bottom of the slide and Cat’s son, Kieron, was hauling him to his feet. The boys high-fived a little clumsily, then ran towards the climbing frame, shouting and laughing.

‘Yeah,’ Cat said, grinning. ‘They’re proper mates.’

‘We can still do this, can’t we?’ Maria asked. ‘After you’ve gone.’

‘Haven’t gone anywhere, yet.’ Cat sipped the tea bought from the small cafeteria near the entrance. ‘Might all fall through, anyway.’

Maria looked at her, as though there might be something her friend hadn’t told her.

‘I mean, these things happen, don’t they? All I’m saying. Some form not filled in properly or whatever.’

‘Presuming it doesn’t, though,’ Maria said. ‘It would be such a shame if we can’t still bring them here.’ She looked back towards the playground, where the two boys were waving from the top of the wooden climbing frame. The women waved back and, almost in unison, they shouted across, urging their children to be careful. ‘They do love it.’

‘Well, it’s not like I’ll be going far.’

‘I’d hate that,’ Maria said.

Cat smiled and leaned against her. ‘You can always bring Josh over to the new place. Put your lazy arse in the car. There are decent parks in Walthamstow.’

‘This is our special place though,’ Maria said. ‘Their special place.’

An elderly woman they

often saw in the wood walked by with her little dog and, as always, the boys rushed across to make a fuss of it. Cat and Maria sat and listened while the woman talked about how nice it was to get out and about, now the warm weather had kicked in, and told them about the campaign to install new bird-feeders and bat-boxes. She stayed chatting for a few minutes more, even after the boys had lost interest and gone back inside the playground, before finally saying goodbye.

‘How’s Josh doing at school?’ Cat asked.

Maria shrugged. ‘Could be better, but I think things are improving.’

‘That’s good.’

‘Kieron?’

‘Well, he’s still missing Josh. Still saying it’s unfair they can’t be at the same school.’

‘It is unfair.’ Maria shook her head, annoyed. ‘You know, a neighbour of mine went out and bought one of those measuring wheels. Walked it all the way from her front door to the school gates, trying to persuade the council she was in the catchment area. A hundred feet short, apparently. It’s ridiculous . . . ’

‘He shouldn’t be there for too much longer anyway,’ Cat said.

‘Right.’

‘Fingers crossed.’

‘What about schools near the new place?’

‘Yeah, pretty good. Best one’s only fifteen minutes’ walk from the flat, but it’s C of E.’ Cat shuddered. ‘Got to convince them I’m a full-time God-botherer if he’s going to get in there.’

‘You must know a few hymns,’ Maria said.

‘“All Things Bright and Beautiful”, that’s about my lot. Not sure I can be doing with all that stuff, anyway. When I went to have a look round, one of the other mums had a moustache Magnum would have been proud of.’

‘What?’

‘Something about not interfering with what the Lord had given her, apparently.’

‘You’re kidding.’

‘Mental, right? Anyhow, there’s another school a bus-ride away, so it’ll be fine. It’ll all work out.’ She stood up and brushed crumbs of blossom from the back of her jeans. ‘Right, I’m desperate for a pee . . . ’

‘Pizza when you get back?’

Cat stared across at her son and his best friend.

The boys were walking slowly around the edge of the playground, in step together and deep in what looked like a very serious conversation. Josh raised his arms and shook his head. Kieron did exactly the same. They were almost certainly talking about Rugrats, but they might have been discussing the Mad Cow crisis or growing tensions in the Middle East.

Cry Baby

Cry Baby